The Road to Emancipation in Jamaica: Rebellion & Reform

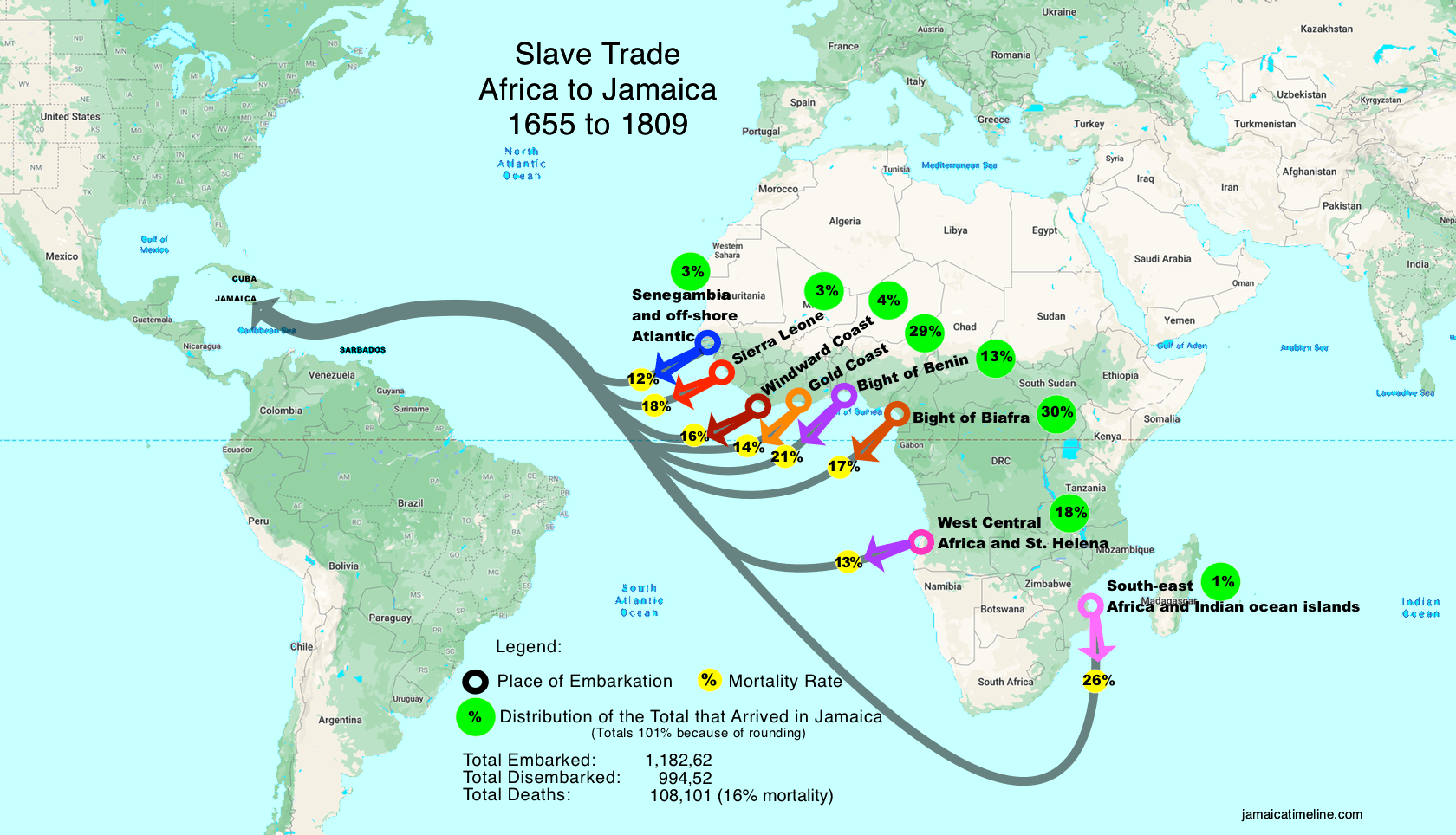

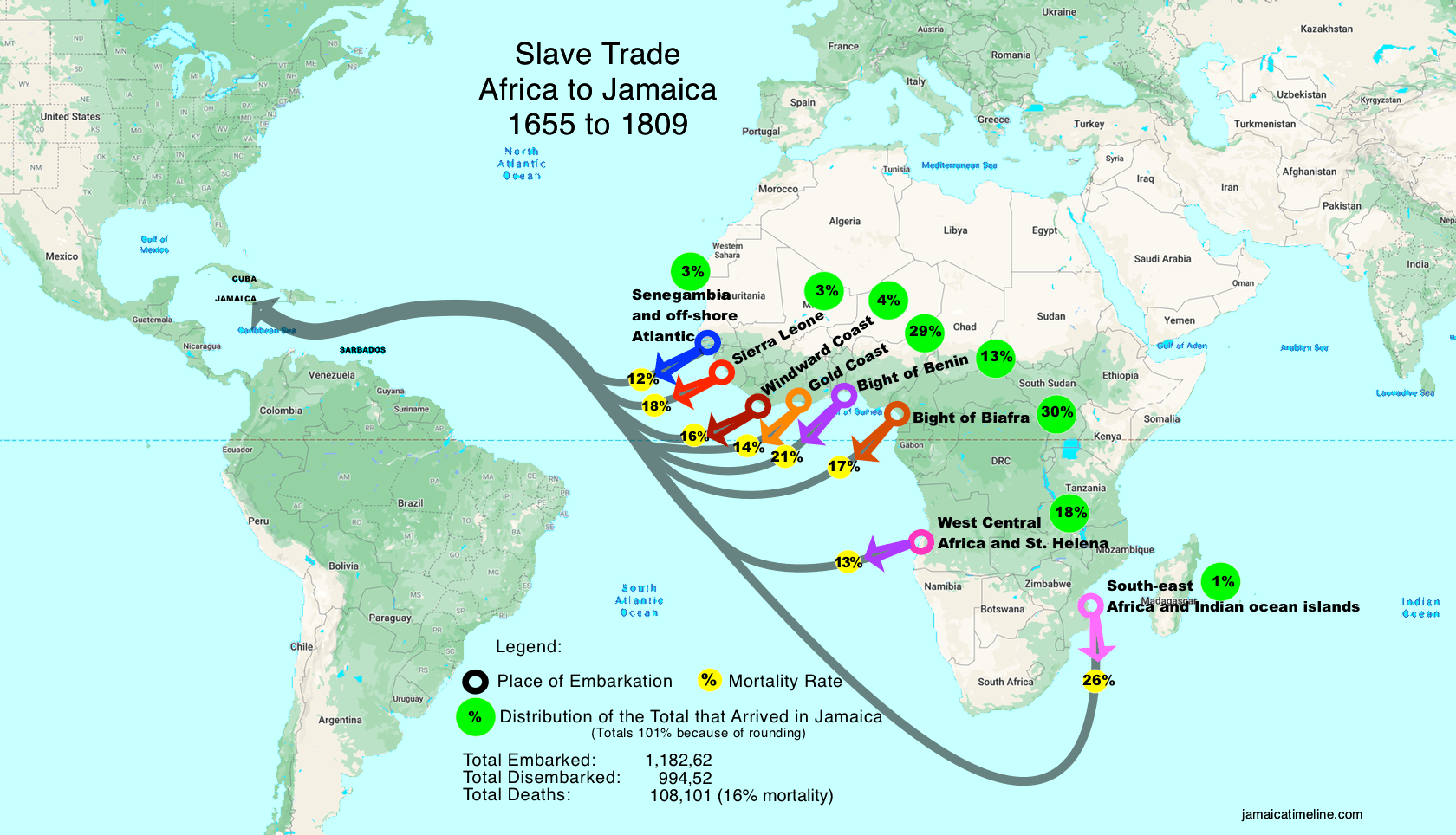

Developed from raw data pulled from the Slave Voyages Database. Percentages are rounded, so >100 for the distribution of arrived.

Introduction

The path to emancipation in Jamaica was shaped by centuries of resistance, economic shifts, and growing abolitionist sentiment in Britain. Enslaved Africans endured brutal exploitation under both Spanish and British rule. Jamaica was a major hub in the transatlantic slave trade, and many Africans were brought there before being sold and transported to other Caribbean islands and parts of the Americas. Over the course of the island's history, the number of enslaved Africans brought to and retained in Jamaica is generally estimated to be between 750,000 and 1.2 million. From the relentless struggles of the enslaved to the shifting economic and political landscape in Britain, emancipation was neither a sudden nor benevolent act. This article explores the socio-political climate leading up to the abolition of slavery, the passage of the Emancipation Act, and its subsequent implementation in Jamaica.

1. The Lead-up to Emancipation

Resistance and Rebellions

Jamaica was one of the most profitable yet brutal slave societies in the British Empire. By the late 18th century, sugar plantations dominated the economy, built on the backs of enslaved Africans who continuously resisted their oppression through both passive and active means:

- Marronage and Uprisings: The Maroons, communities of escaped enslaved people, waged guerrilla warfare against the British throughout the 18th century. Their resistance led to the signing of treaties in 1739 and 1740, granting them semi-autonomous status but also obligating them to return runaway slaves to British authorities. While some Maroons upheld these treaty obligations, others covertly aided runaways. The Maroons themselves were not a unified group, and internal divisions existed regarding their relationship with the British.

- Tacky’s War (1760): One of the earliest large-scale revolts, this rebellion saw enslaved Africans seize plantations and weapons before being brutally suppressed.

- The Baptist War (1831-1832): Led by Samuel Sharpe, this was the largest rebellion in Jamaica’s history. Initially a peaceful strike for wages, it escalated into widespread resistance, involving over 60,000 enslaved people. The violent suppression of this revolt, which led to the execution of Sharpe and over 500 others, shocked British society and fueled the abolitionist movement.

Economic Shifts and the Decline of Slavery

By the early 19th century, slavery was becoming less economically viable in certain sectors. Several factors contributed to its decline:

- The Industrial Revolution in Britain led to a shift in economic priorities, reducing reliance on slave-based agriculture.

- The Abolition of the Slave Trade Act (1807) curtailed the importation of new enslaved people, making plantation labor more expensive.

- The Decline of the Sugar Economy: Increased competition from other colonies and changes in the global market made sugar less profitable, reducing the economic justification for slavery. Some planters attempted to adapt by diversifying into crops like coffee and pimento, though these efforts had limited success.

- The Rising Cost of Suppression: Rebellions such as the Baptist War demonstrated the growing instability of the slave system, making its maintenance increasingly costly for Britain.

- The humanitarian efforts of abolitionists such as William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson placed increasing pressure on Parliament to end slavery.

- The British government responded to mounting pressure by forming committees to investigate slavery in the colonies. Reports detailing the harsh conditions faced by enslaved people, coupled with moral arguments from Christian missionaries and dissenters—some of whom supported gradual rather than immediate abolition—swayed public opinion. The aftermath of the Baptist War further underscored the untenability of slavery, prompting Parliament to act.

2. The Passage of the Slavery Abolition Act (1833)

The Slavery Abolition Act was passed by the British Parliament on August 28, 1833, receiving royal assent shortly thereafter. It came into effect on August 1, 1834, formally abolishing slavery across most of the British Empire. However, emancipation was not immediate or absolute; instead, the act introduced a transitional system known as "apprenticeship."

Key provisions of the act included:

- The gradual abolition of slavery, requiring enslaved individuals over six years old to continue working for their former masters for four to six years without pay.

- A £20 million compensation package paid to slave owners, funded by British taxpayers. This equated to 40% of Britain's national budget at the time. Absentee landlords in Britain disproportionately benefited from this, while formerly enslaved individuals received nothing.

- The establishment of an apprenticeship system, designed to maintain plantation productivity while gradually transitioning enslaved people into wage laborers.

Despite resistance from planters and colonial elites, the act was passed, marking a legal, albeit flawed, end to slavery in the British Empire.

3. The Rollout of Emancipation in Jamaica

The Apprenticeship System (1834-1838)

Instead of immediate freedom, formerly enslaved Jamaicans were forced into an apprenticeship system:

- Apprentices were required to work 40 hours per week without pay, with the promise of food, clothing, lodging, and medical care.

- They could work additional hours for wages to purchase their freedom, but they faced severe exploitation and harsh punishments from magistrates overseeing the system.

- Special magistrates were appointed to mediate disputes between apprentices and former masters, but they often sided with plantation owners, perpetuating injustices.

- Widespread resistance, including strikes and protests, demonstrated the deep dissatisfaction with this system.

- Some apprentices successfully petitioned for early release before 1838, contributing to the pressure to end the system sooner than planned. However, widespread resistance and reports of abuse, rather than individual petitions alone, led to the system’s premature termination. On August 1, 1838—four years ahead of schedule—all apprentices were granted full freedom after sustained protests and lobbying efforts.

The apprenticeship system was widely unpopular and met with resistance. Reports of continued abuses and protests led to its premature termination. On August 1, 1838—four years ahead of schedule—all apprentices were granted full freedom after sustained protests and lobbying efforts.

Full Emancipation and Its Aftermath

On August 1, 1838, approximately 311,000 formerly enslaved people in Jamaica celebrated their newfound freedom. Churches and town centers became sites of joyous gatherings as emancipation declarations were read aloud. However, emancipation brought new challenges:

- Economic Displacement: Freed individuals often lacked access to land or resources. Many became wage laborers on plantations under exploitative conditions or moved to "free villages"—settlements established by missionaries.

- Social Tensions: Racial hierarchies persisted despite legal freedom, and formerly enslaved people struggled against systemic discrimination and economic inequality.

- New Labor Laws: These laws heavily favored former slave owners, ensuring continued economic control over the newly freed population.

- Rise of a Peasant Economy: Many freed Jamaicans sought to acquire land and build self-sufficient farming communities, resisting continued economic dependency on plantation labor. While some had to work for low wages on estates, others pooled resources to purchase land, leading to the rise of small-scale independent farming. This marked the foundation of Jamaica’s emerging peasant economy, which provided a degree of economic autonomy and laid the groundwork for rural agricultural communities that exist today.

While emancipation ended legal slavery, deep inequalities remained. The plantation economy continued to dominate, and former slaves faced ongoing struggles for economic independence and social justice.

Conclusion

The journey to emancipation in Jamaica was long and arduous, driven by the resilience of enslaved Africans and the efforts of abolitionists. While the passage of the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 marked a crucial turning point, the realities of freedom were far from ideal. The legacy of slavery’s abolition continues to shape Jamaica’s society, influencing its economic structures and cultural identity to this day.

By understanding the full scope of emancipation’s journey—from rebellion to legislation to its flawed implementation—we gain a deeper appreciation for the resilience and agency of those who fought for freedom.