While the story of the Windrush Generation is often anchored to the summer of 1948, the movement itself was forged earlier, in the material hardships of a post-war Jamaica under severe strain. By 1947, the island had become an economic pressure cooker. More than 10,000 World War II veterans returned home to find jobs scarce, while agriculture—the backbone of the rural economy—was still reeling from the Great Hurricane of 1944, which had wiped out roughly 90 percent of the banana industry and nearly half of all coconut production. For many skilled and ambitious Jamaicans, the choice was stark: remain in an economy that could no longer sustain them, or return to the “Mother Country” they had recently helped defend.

This Jamaican desperation coincided with a Britain equally in need. War-weary and damaged, the country faced an acute labor shortage as it rebuilt its cities, restored transport networks, and prepared to launch the National Health Service. In 1947, the first vanguard of migrants answered this call. A full year before the iconic arrival of the Empire Windrush, ships such as the Ormonde and the Almanzora carried organized groups of pioneers to Liverpool and Southampton. These early crossings became the proving ground for the mass migration that followed—one that would irrevocably reshape both Jamaica and Britain.

The Windrush Generation trace their name to the HMT Empire Windrush, which arrived at Tilbury, England on 22 June 1948 carrying one of the first large groups of West Indian migrants to Britain—most from Jamaica, alongside others from Barbados, Trinidad & Tobago, and smaller Caribbean islands. Their story is not only about that first wave of settlers but also about the children and grandchildren who followed, born in Britain yet inheriting both the struggles and achievements of their parents.

This history is one of post-war rebuilding, resilience, and a test of Britain’s promise to its Commonwealth citizens. In the decades after 1948, tens of thousands crossed the Atlantic to fill labor shortages and build new lives in Britain. These pioneers arrived as British subjects entitled to citizenship rights, yet they often found themselves confronting discrimination, exploitative housing markets, and cultural barriers. Later generations—born or raised in Britain—would grow up negotiating dual identities, shaping British society, politics, and culture in ways that remain profound today. This report explores why they came, how they settled, the challenges faced over generations, and the scandal that drew renewed attention decades later.

Britain’s post-war reconstruction created acute labor shortages. At the same time, the British Nationality Act 1948 recognized all Citizens of the UK and Colonies (CUKCs) as British, permitting them to live and work in the UK without visas. Many early arrivals had served in the armed forces; others were young workers who responded to recruitment drives and informal encouragement from British employers.

Through the 1950s, the UK remained open to Commonwealth migration. By the early 1960s, however, attitudes and laws shifted. The Commonwealth Immigrants Acts (1962, 1968) and the Immigration Act (1971) restricted entry and introduced “patriality.” Crucially, the 1971 Act gave Commonwealth citizens already resident—many of them parents of the second Windrush generation—indefinite leave to remain.

After 1945, Britain urgently needed workers for the new NHS―National Health Service (founded 1948), public transport, railways, construction, and manufacturing. While early efforts recruited displaced Europeans, demand far exceeded supply. British bodies then looked to the Commonwealth: English-speaking, culturally Britain-facing Caribbean citizens with full work rights.

Formal and informal recruitment followed. The NHS and Ministry of Health supported direct recruitment of Caribbean nurses and auxiliaries. London Transport sent teams to the Caribbean to hire bus and Underground staff. By the 1960s, the fabric of Britain’s public services and industries was interwoven with Windrush migrants.

Migrants initially settled where work was available: London (Brixton, Notting Hill, Hackney, Tottenham), Birmingham (Handsworth), Manchester (Moss Side), Nottingham, Bristol, and Leeds. Housing shortages and racial discrimination left many facing exploitative landlords and “No Blacks, No Irish, No Dogs” policies. Churches, island associations, and grassroots organizations became lifelines. Their children grew up in these urban communities, helping shape Britain’s multicultural neighborhoods of the 1960s–80s.

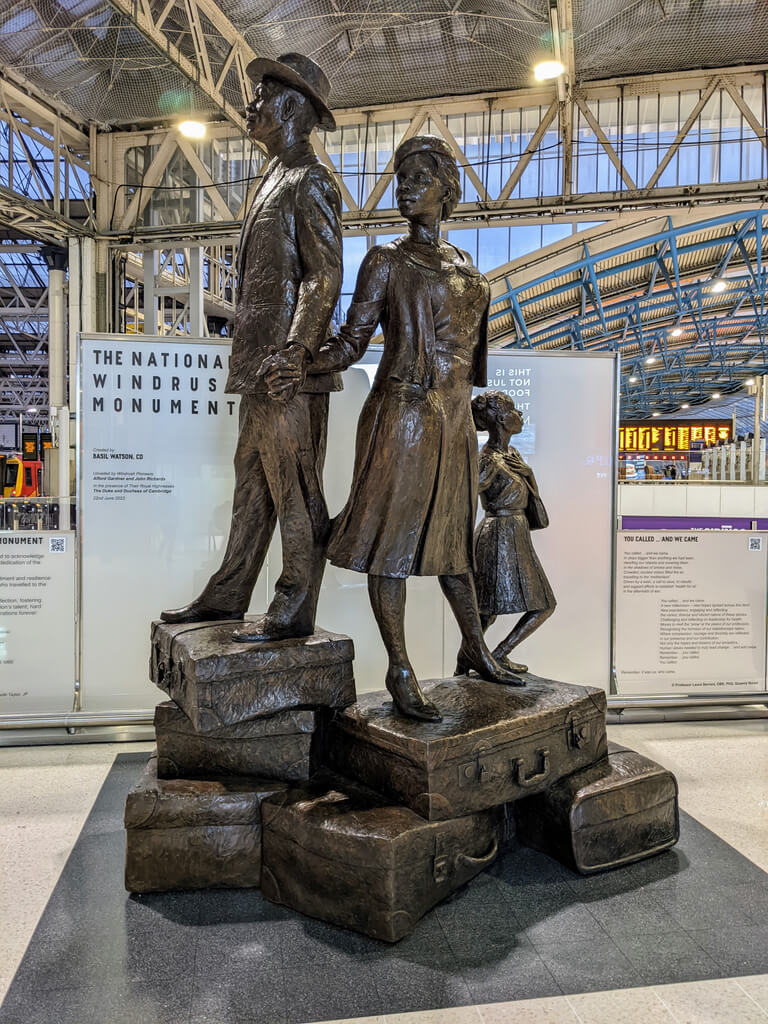

National Windrush Monument,

Waterloo Station, Lomdon

Employment Patterns:

Despite prior skills, many first generation immigrants accepted lower-paid or manual roles due to credential barriers and discriminatory hiring. Nevertheless, employment rates among arrivals were high because demand was high.

Reactions to the Windrush Generations were mixed. Many Britons welcomed their contributions, but others responded with hostility. The Notting Hill and Nottingham riots (1958) and the murder of Kelso Cochrane (1959) underscored racial tensions. Still, activism and cultural self-expression flourished. The origins of Notting Hill Carnival, popular Caribbean music (ska, reggae, calypso), and political mobilization all emerged from Windrush-era families and were carried forward by their descendants.

The Race Relations Acts (1965, 1968, 1976) slowly established protections against discrimination, though enforcement was often weak. Later Windrush-born generations played leading roles in campaigns for racial justice, educational reform, and representation in political institutions.

As British subjects, Windrush migrants could access the NHS, public education, and social security on the same basis as others—and they paid taxes to support those systems. Practical integration support was minimal in the 1950s; community organisations filled gaps. From the mid-1960s, public bodies (Race/Community Relations Boards; later the Commission for Racial Equality) and anti-discrimination law provided some recourse, though enforcement and outcomes were uneven.

The Immigration Act 1971 granted indefinite leave to remain to Commonwealth citizens resident by 1973, but many never received documentary proof. Decades later, the UK’s “Hostile Environment” policies (from 2012) required people to prove status to work, rent, bank, or access healthcare. The 2010 destruction of historical landing records compounded proof problems. Long-settled, lawful residents—often who had arrived as children on parents’ documents—were suddenly unable to evidence their status.

The government accepted the review’s recommendations and launched reform and training initiatives; Windrush Day (22 June) became an annual commemoration; in 2022 a National Windrush Monument was unveiled at London Waterloo. The compensation scheme has faced strong criticism for complexity and delay, with continuing calls for independent administration and full implementation of reforms. Community advocacy and parliamentary oversight remain active.

| Years | Event |

|---|---|

| 1948 | Empire Windrush arrives; the British Nationality Act 1948 creates the status of Citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies (CUKC). Until 1962, most Commonwealth citizens could enter, live and work in the UK without visas. |

| 1958–1959 | Notting Hill & Nottingham disturbances; murder of Kelso Cochrane(1); rise in anti-racist activism and community organising. |

| 1962 | Commonwealth Immigrants Act introduces entry vouchers, curbing free movement. |

| 1965/1968/1976 | Race Relations Acts progressively outlaw racial discrimination and establish enforcement bodies. |

| 1968 | Commonwealth Immigrants Act further restricts entry; heightened public and political debate. |

| 1971/1973 | Immigration Act 1971 (in force 1 Jan 1973) introduces patriality(2) / right of abode and grants indefinite leave to remain to Commonwealth citizens already resident by that date. |

| 1981 | British Nationality Act ends CUKC status and creates new citizenship categories; provides registration/naturalisation routes for residents. |

(1)Context: Kelso Cochrane, a 32-year-old Antiguan carpenter, was fatally stabbed by a group of white youths in Notting Hill on 17 May 1959. No one was convicted. The killing—widely understood as racially motivated despite an initial police claim of robbery—became a rallying point for anti-racist organising and community solidarity in West London.

(2) Being a CUKC did not automatically confer the UK right of abode. Under the Immigration Act 1971 (in force 1 Jan 1973), a CUKC had right of abode only if they had a UK-born parent or a UK-born grandparent.

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 2012 | “Hostile Environment” measures require proof of status for work, renting, banking, healthcare. |

| 2017‑2018 | Investigations expose wrongful detentions/deportations; official apologies; Windrush Taskforce and Compensation Scheme announced. |

| 2020 | Windrush Lessons Learned Review published; 30 recommendations accepted; formal apology reiterated. |

| 2022 | National Windrush Monument unveiled at London Waterloo; continuing scrutiny of compensation and reform progress. |

| 2023‑2025 | Ongoing redress and oversight; continued debate over compensation performance and policy change. |

The Windrush story is one of hope, labor, and endurance. Jamaican and wider Caribbean migrants were indispensable to Britain’s post-war recovery and cultural life, even as they faced systemic barriers. The recent scandal underscores how administrative amnesia and hard-line enforcement can upend settled lives. Recognition (Windrush Day, the monument) and reform are meaningful; full justice requires continued delivery on compensation and structural change.